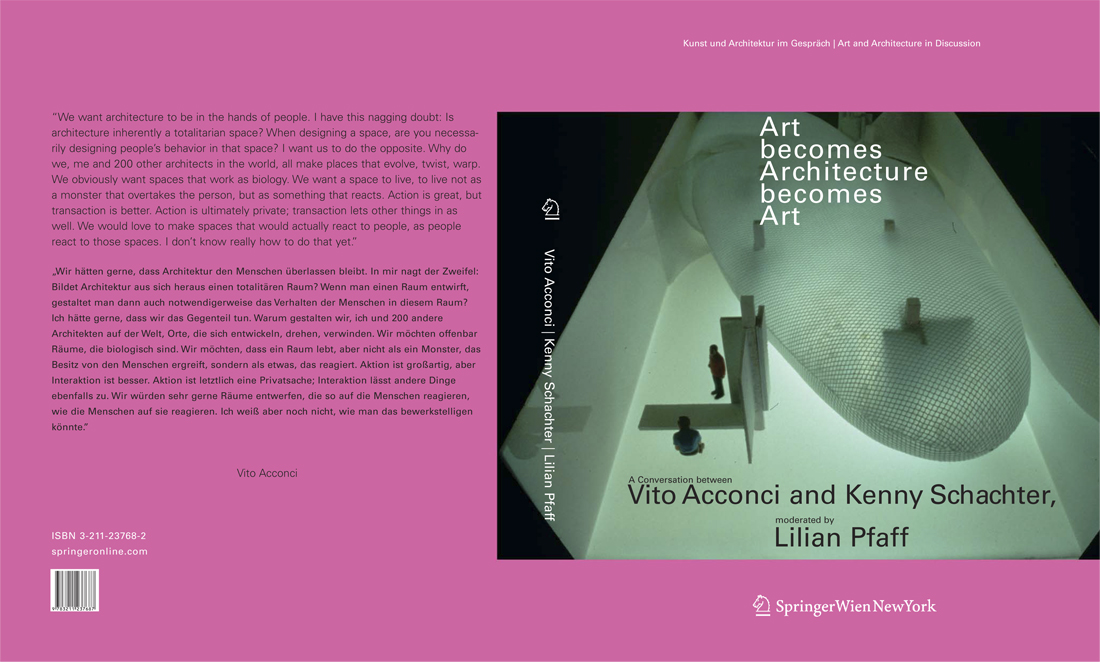

ART BECOMES ARCHITECTURE BECOMES ART:

moderated by Lilian Pfaff.

Lilian Pfaff: The gallery "Kenny Schachter Contemporary" is a joint project. Was it a shared collaboration or more of a client -- architect relationship?

Vito Acconci: I think it's somewhere in between. Client-architect working-relations tend always towards collaboration. In a sense, the one thing we crave, when we work with clients, is to find out what they think, what they want. That gives us a starting point. I'm not sure if Kenny told us what he wanted, but he told us an awful lot about what he didn't want, about what he hated. It wasn't a collaboration in the sense that Kenny worked with us as we designed. But we showed Kenny a lot of things as we progressed. He talked a lot about the relation of the street and the gallery. He hated the idea of the street ending and the gallery beginning. And at the same time he brought up the fact that that the side of the gallery in New York was on an alley where a lot of things are going on. People fuck, people get blow jobs, and people take drugs. He wants the street to extend into the gallery. However, the gallery is part of his house, he has kids, and he doesn't exactly want this stuff. So he gave us confusion. We want to connect to the street, but we can't connect to this particular street, so what do we do as an alternative?

Kenny Schachter: But we even started before that. Our first liaison together was regarding a kind of theoretical space. We started speaking together about me not knowing exactly what I wanted. We didn't even have a concrete space yet. Really it was just fleshing out the notion of a radical departure from the typical way that exhibition spaces are designed. The first part was this theoretical gallery, a model came from it; from there we went to the actual gallery we built, and then we did three booths for art fairs together.

VA: We started by thinking: let's think of a gallery before we think of art. So it is a place without walls, without floors, without ceilings. You walk into a void and then you have a floor where you need it, you have a ceiling where you need it. Could that really have been done? I'm not so sure. But at the same time we weren't worrying so much about what really could be done. I think Kenny asked us to do a model, not of a gallery, but of an idea of a gallery, because I think he thought that from there on we could talk. He knew what his ideas of a gallery were and wanted to see what our ideas were like. He set the stage for something that we always set up in the studio: discussion, and the discussion can be an argument, maybe an antagonism, maybe not, but at least collision and I think collision is important. When we work in the studio we throw around a lot of ideas, we agree, we disagree. I don't think the goal is resolution; the goal is more a collection of disparate elements that remain somewhat disparate because if things become too resolved, it is a closed system.

LP: But you did decide to work with an existing space.

VA: One of the reasons why we gravitated towards the notion of an existing New York space was that it gave us columns. So we had starting points for walls, ceilings, and furniture. All the parts of walls, floors, and ceilings would be folded and stacked onto the columns. You could pull out an entire floor or only the amount of floor and wall that you wanted. I don't know if we carried that through enough, but we at least introduced the potential.

KS: It was almost like a shell, but a more abstract shell. The walls would come out of the column, accordion-style. There wasn't a given. In an exhibition space you take for granted that there are four walls and a floor and a ceiling. But in this case, basically none of these things existed. You could pull down a wall, whatever the need was.

VA: Then, after that, we became more open; we thought about bringing the street into the gallery. No matter what building this gallery is, it would have to have some kind of façade. Could we literally suck the façade in? As you walk, you walk into the interior of a shell, the skin of the gallery wraps around the viewers as they walk into it.

KS: In the beginning, when Vito brought up the idea of actually bringing the sidewalk into the space, the initial notion was that there would be no façade during opening hours, just a wide open interface between public and private.

VA: We hoped that we could use some kind of climate control.

KS: Rem Koolhaas just did a store for Prada in Los Angeles and he got hold of the technology and instituted this invisible curtain wall, a heat curtain wall of thermal insulation that separates the outside weather from the inside.

VA: Even with the heat screen you need some kind of a security screen. Even the Prada store comes down at night, unless the heat were to become unbearable fire.

KS: We started in January 2001. I was trying to raise money for the building, but this fell through because of the frenzy in the real estate market. So I was faced with either stopping or waiting. I decided to carve a venue out of a section of my living space. There were two entrances to my house, one on Charles Street and the other on this little alleyway, Charles Lane. It fit perfectly into one of the issues that Vito is constantly dealing with in his work as well—the separation of public and private. I worked as a curator for 15 years organizing exhibitions in lots of different spaces and I always kept the doors open and I was always interested in this kind of critique of the gallery. I would never put the word gallery on the door because I think you are pigeonholing yourself by triggering a set of very explicit expectations in people. And despite the fact that gallery-going is the only free lunch in town, you are basically turning away 95% of the general public when they see the word gallery because they are completely turned off by the exclusionary sterile atmosphere that they know they will encounter. Galleries all over the world look the same, the mindset is the same, too, and the structure the same. What we wanted to do is to start from a different point. I didn't want to stick to all those unwritten laws that everybody abides by. We went about deconstructing that without taking anything for granted. There was the space, and there were two sides to it. There was a separation to my family, my kids and my life on the backside, and then there was a separation on the front side, with the street and the public.

VA: We never dealt with the street enough. We set up a steel wall—ok it was diagonal, it went into the gallery, it was the basis of the rest of the gallery, but in some ways it was a barrier.

KS: With all the activity that went on in the alleyway, I'm glad we did have a steel barrier! But it was the door that really began this process of continuity between the elements inside the space. It jutted out into the public space, so that instead of bringing things into the architecture of the gallery, the gallery transgressed or encroached into the public space.

VA: We started with a piece of steel. You need a door so you cut into that piece of steel and you have the entrance of the gallery. When that piece of steel went inside the gallery, it could split and twist: it could become a shutter for the window on the front wall, or it could become the reception desk or the seat for the receptionist.

LP: Like the Storefront?

VA: The Storefront is a project I love and hate at the same time. Because it's 50% a good project. But it's in New York, which makes it a good project for spring and summer and a terrible one for fall and winter, so I think in some ways it is an irresponsible project. The idea of opening something up, which I still love, ignores the fact that there is a climate, that there is weather. Architecture exists because nature is possibly dangerous. Again Acconci Studio didn't do it alone; it was a kind of collaboration with Steven Holl—an Acconci Studio/Steven Holl project. Interestingly we cared more about the weather than Steven did. Steven is used to working as an architect and wanted to work as an artist; I wanted to work as an architect.

For us it was almost our first chance to do real architecture and we let budget get in the way, a very small budget, it was $50,000, but I don't think budget is ever an excuse. You cannot say, well I didn't put walls up because we didn't have any money. You have to find a way to put walls up with no money, otherwise you're just doing what I always think artists do: they make-believe versions of their things, they make-believe films, they make-believe architecture; it's all play. Which is, I think, the way my stuff started…

LP: To what extent did Frederick Kiesler serve as a model?

VA: Kenny had Kiesler in mind. I don't think I knew much about him.

KS: Frederick Kiesler designed Peggy Guggenheim's Art of This Century Gallery that opened in 1942. To me it was a carnivalesque wonderland of inspiration. I think there are many parallels between Kiesler and Vito. Like Vito, Kiesler was a man of varied and eclectic tastes and talents, from architecture and furniture design to stage sets and room-sized art installations. He was a dilettante to some and a maverick to others. Kiesler wrote on the philosophy of the storefront in the early 1930s; Vito has written extensively on his own work and also designed a storefront. Kiesler's gallery design was fantastic and unusual, like a children's playpen within which to experience art. Such a feat has not been repeated, or for that matter attempted, since. The world of the gallery today is a static, hermetically sealed universe opened mainly to the insiders who participate in and run it. It is a business, first and foremost. I see nothing wrong with the economics of art, in fact I appreciate the business aspect as the only way to achieve transparency in the machinations of the endeavor, but I just don't believe art is solely reducible to money.

LP: Why does this gallery interest you in particular?

KS: I was mainly interested in the furniture elements of the Art of This Century Gallery, in the walls that curved and had different functions. There was a device where you could turn a handle and a little table would circle with Paul Klee paintings on it. Paintings were displayed cantilevered off the walls with baseball bats, so they would be viewed on an angle facing downward. Some artists exhibiting in Kiesler's space were unhappy because one of the designs that he initially conceived had lights that would go on and off. So if you were standing in front of a painting, the light would shine on that painting and then it would go off and move to another painting.

KS: Galleries in the past had seating, etc.; they looked like somebody's private salon. So either you put work in a space that looks like somebody's living room, or you put it in a space that kind of apes museum spaces, which would afford the art more credibility and legitimacy. But then the notion became loaded. Instead of being just a neutral environment in which to look at art, it turned into an economic manifestation where the reception desks are so high you can't even see over them. It's all about drawing lines of exclusion, and the art world used to function on the basis of that premise. There are certain things happening now that are changing this, in spite of the art world's mentality (like the proliferation of fairs).

VA: I think these galleries didn't start out wanting to create austerity. They just didn't want the gallery to be modeled on something like a rich person's home; the aim was to have it be a laboratory space in which anything could happen. Maybe it was just a pretense, but it was also the appropriate space where Minimal Art could be exhibited. It was never a neutral space—well, no space can be neutral—but at the beginning, it did offer the possibility of an open space where you weren't restricted by the domestic signs of a collector. Then it became a kind of standard.

KS: They all look the same. It's taken for granted that this is the formula. Now it's a wealthy collector's white cube space. I wanted to do some kind of knee-jerk reaction away from that. Maybe what we ended up with wasn't even the best place to display art, but that wasn't the point. It was about this experimental thing, like what you said about galleries in the fifties and sixties, except that it's very different now, there's no connection.

LP: Both you and Kiesler talk about movable furniture. But the furniture in the Kenny Schachter Contemporary Gallery is totally immobile.

VA: We didn't want it to be that heavy; we got ourselves into a kind of bind, I think. There was a limited budget. We knew it was a temporary gallery. So, since we couldn't change the walls, we tried to figure out a way to cover them, to screen them. The material that was open and strong enough to hold something was expanded metal, but it was also a bit clumsy.

KS: For me it was important to have seating. I've always been interested in reaching new audiences and creating a welcoming environment conducive to spending more time at a venue. Also with the temporary exhibitions I curated, I always brought in furniture. One of the most successful elements in Vito's space was that the walls morphed. There were elements of the walls that folded up to create seating. From time to time, they would fall off the wall, fall apart or something (knock someone in the head even!). But they functioned, and were utilized non-stop from the beginning to the end of the space. And they weren't heavy or difficult to manage individually, but at 35,000 pounds of steel for the whole thing, it was a bit more than initially contemplated for a temporary space.

VA: They were a little heavier than they should have been and the seats hinge down from the wall. People were always sitting next to each other in a row, almost like at an airport. Maybe that explains why furniture is usually mobile.

KS: But it almost looked like this thing was just implanted in the house. Maybe the desks ended up being quite weighty, but altogether I think it functioned in a wonderful way. I can't think of one negative aspect, of one thing that failed other than the fact that I had this gigantic thing weighing down my house and almost making it sink into the earth--and then the slight problem of my having moved to London (the main contents of the gallery—the front door connected to the desk and window shutter and upstairs office were sold at the Phillips design auction in December of 2004).

Cristina Bechtler: There is also a sculptural aspect to the desk.

VA: None of us want that. We don't want an artwork. The worst thing anybody can say is that it is sculptural. When we're working on something and we don't like it, somebody in the studio will say it's sculptural.

KS: I think there are two sides to this. Number one: It's unavoidable. Number two: When you or anyone with an architectural project creates a form, it has certain attributes, a sculptural aspect.

VA: But every millimeter of that form should be able to be used.

KS: But you're kind of jaded, we know your reactionary position with regard to art. I remember this young artist, when I first talked to her—she was a young kid at Columbia, just graduating, a painter—about doing an exhibition, she was so excited at the prospect of working in your space, but when push came to shove, she recoiled from the thought of presenting her work in this context.

VA: There were two comments people tended to make. Some said that the space would overwhelm anything that was in it. And others thought the space would work better for music performances—which struck me even more. I keep asking myself about this. About the space taking over, I hope it doesn't.

KS: I disagree totally. I lived in that space everyday; for three years I presented exhibitions and many performative or music events with people like Kim Gordon and Thurston Moore of Sonic Youth. To me it was thrilling to see different types of work unfold in the Acconci interior. There was one artist in particular, a Japanese woman, Misaki Kawai. She made an installation of all these elements suspended from the ceiling, and then her idea was to tape fabric clouds onto the wall, but since the tape wouldn't take to the steel, she attached the clouds individually through the mesh with thread. To me that was such a beautiful progression, such a beautiful example of the give and take involved in working in the space. It was, in essence, the perfect relationship between art, artist and space.

VA: I hoped that if we used really conventional industrial materials, the place would have a kind of factory feel.

LP: When you worked as an artist, would you have been disturbed by this kind of space that you've made?

VA: Probably not. Because I've always liked to figure out the quirks of a space and this space had so many quirks. I was the kind of artist who didn't have something I wanted to show. I never had a piece in mind until I saw the space. The space would always engender the piece. But that's only one approach to art within a whole field or a whole network of different kinds of art. Someone like me would probably have been perfect for the space, but I'm not the only example.

KS: Some people really rose to the occasion. Like the abstract painter Mary Heilmann. She was thrilled to work in that thing. It can inspire people. A gallery is not the ultimate resting space for art, so why not do something that's more adventurous.

VA: But you've even said that you sometimes wished the space had more white walls. I can understand that. If we were doing the gallery again, we would think of at least the possibility of white walls, though they might not inevitably and always be there.

LP: It's curious that, after you deliberately turned your back on museums as an artist, you're now involved with museums and exhibitions again. Is this a return to the museum?

VA: No, it isn't. Well, maybe to design a museum, but not to be in one. We were interested in designing spaces for many different functions; we were not particularly drawn to an art space. But these are people we know and have contacts with; they are the only people who would ask us to design spaces.

KS: That's how we met. I was courting Vito; I'd been wanting to present his work for ages. I read all the writings and thought this was very significant work. I was always a fan and made attempts to get in touch, but he never returned a fax or phone call or anything. When I read that Vito was doing architectural projects and was hankering to do anything at that point, even a bathroom, I contacted him and the next day, we started forging our relationship together.

VA: Maybe it did give the studio, and me a chance—why did I feel so uncomfortable in the art world?—to find a way to make a platform, a showcase for art more like a city street, less like the conventional gallery or museum: different kinds of spaces, open spaces, closed spaces, different kinds of occasions to gravitate to. That's still a project that's very close to me!

CB: What territories do you share?

KS.: The correlation between my practice and that of Vito and his studio is that I was never comfortable with the black-and-white, pre-defined roles of the art world. Also, I am constantly changing and mutating what I do and how I do it. Also, I am perfectly in agreement with Vito on the blurring of distinctions: why not cloud the idea of what is inside versus outside, public versus private.

The way the studio works, and the way we have worked together, is to establish a give and take, back and forth, an ongoing dialogue where things are discussed, sometimes argumentatively, then acted upon. And often times, because of Vito's position with regard to his abandoning doing art, I almost sense a kind of not antagonism per se, but some ambivalence about the art world. It's been years since he totally left that world altogether. So it's a funny thing because, when I first approached the studio, it was with something completely different from the temporary exhibition space in New York. The idea was to build a big gallery, a more ambitious enterprise in a very public space in New York, and there is a certain inherent problem (or humor!) in something like that, i.e. working with someone who has a caginess about art to design a venue specifically geared to showcase it.

LP: That reminds me of your work at MAK in Vienna when you turned the exhibition space upside down and destroyed the museum. Was that the end of your art career and the beginning of the architecture?

VA: It was probably the starting point. Maybe an end point and a starting point at the same time. But there we weren't doing a museum renovation, we were doing a piece in a museum. MAK had been closed for two years for renovation, so we did a kind of re-renovation. I think we had Peter Noever, the director, in mind, when we did that piece at MAK. Peter likes to think of himself as a kind of bad boy in Vienna. So we did exactly what Peter Noever would have done: we opened the museum by turning it inside out and upside down.

LP: How does that relate to the museum shop, which you also designed for MAK?

VA: Our starting point was the fact that there would be two kinds of products in the store. They told us that some of the products would be very cheap, so people could easily touch them. But others would be very expensive and could not be touched, which made us think in terms of desire.

KS: At the Guggenheim in Soho you used to have to enter the shop before you even got into the museum. It is social engineering where there is a manipulation going on, an agenda: let's get them in to buy before their minds are unnecessarily cluttered and muddled (and attention spans shortened) by having to look at all the art. But back to the initial concept of desire where, more often than not, you can't always get what you want.

VA: Yes, since you can't always have what you want, we made this store of rings. Every other ring is made of perforated metal shelves where you can just take things. The alternating rings are enclosed in glass and are constantly rotating so that you might see something you want to your left, but then it goes above your head, or it goes away for a while under your feet, or maybe it comes back. Wherever you are, even when you are at the counter, there are more products coming around you. Two of the rings go outside, through the window, so you don't need a sign for the store: because they move outside, the products themselves become a sign. I like the project. It hasn't even been built yet, so I don't know if it's going to happen. But it probably will happen because Peter Noever wants to do it. The problem is that we designed it so long ago that if we do do it, we'll probably have a different idea.

KS: That ties in to some of the stuff that we've been working on for art fairs, creating a structure within which to view art that is more transparent than conventional walls, where the works can be viewed front and back. Sometimes the back of a painting where a history is recorded is as interesting as the front.

LP: What did the booths look like and were they all the same?

KS: For me it kind of started like this: When you go to an art fair, it takes away all the particularities and nuances of an exhibition, including the architecture within which a show is presented, but it's instant gratification. All the booths are uniform, when you walk down the aisles, you get a quick blast of what each gallery has on offer. It's like a bazaar where people lay out their blankets on the street to flog things, and attention spans are limited, so you need to see things that make an impact fast. Being there for ten or twelve hours a day for five days myself manning the booth, I tried to make the experience more interesting by asking: what can you do to unsettle the context, this generic booth that you are given?

VA: One thing we knew, the first time we did an art fair booth for Kenny, was that it is important for him to have some kind of office-like space, some kind of space where you can say: this is a gallery, an art store, where people are going to talk to you and you have to make sales quickly because it's just going to be there for three days. We thought why not make the gallery dealer the central part of the gallery. So we started with Kenny's desk in the middle and it was a kind of circle, a circular seat so that Kenny could be on one side of the table, a client could be on the other side of the table. The back of the chairs were these rods that come up, go over and down onto the wall, so they make a kind of ceiling. And we tried to make the ceiling like a kind of arch. But the arch shifts a little bit to the side, and then it goes to the center. I don't know if anybody even noticed that, but it meant that you were in a kind of space that is moving.

KS: Basically the metal pipes were connected to the top of the existing fair walls. These poles were installed at the top of the wall, then swooped down and curled in on themselves, like a kind of implosion. The structure was covered in this fabric that they use to wrap around scaffolds. In the center of it all, there was a little pod formed by all the poles that supported the fabric and formed an enclosure. The office was just where the poles curled in. But, like Vito said, the import of these fairs is to make a quick relationship with someone and consummate a sale. But in this case I was stuck in the middle, hidden, and then the door was only about three feet wide; so, there was this indescribable fabric thing and I was enclosed in this cocoon in the core: was it sculpture, was it art, was there someone stuck inside there? Once again I succeeded in presenting a perfectly muddled picture. People would pass by. The shape and the form was something to marvel at, it was this absolutely beautiful structure. I am marginalized enough in the art world as it is, but in this case I further alienated myself by being sort of stuck in this little envelope. People would come by and simply walk right past without so much as casting a glance beyond the skin of my little habitat!

VA: The next time we did it, he made us open the space as much as possible. Once we had these crossing fiberglass rods you could immediately see through. It was also a reaction against the background of expanded metal in the Charles Street space.

KS: We tried out a variation that was completely different, but came up short the first time we tried it in Art Basel Miami. In the instance with the Armory, the form sort of gracefully collapsed on itself from the top of the walls, and in the second case (Basel Miami, 2003) the thing violently caved in a non-metaphorical way, nearly taking the whole of the fair down in the process: it collapsed during installation practically killing two people and almost knocking down a row of walls like dominoes.

LP: And you're still working together?

KS: Vito is always challenging himself to do new projects, pushing new ideas and working at things nobody else would do. When you do something outside of your own safe area of expertise, like starting an architecture studio, you are inherently putting yourself at risk: at risk to embarrass yourself, at risk to humiliate yourself in front of your peers, at risk to the public by building a potentially faulty structure. But really, that is the only way to succeed and do exciting things in life, making advances just by pushing into areas where there is no level of security or comfortableness, no safety net. When you set yourself up for accidents: that's when innovations are born.

LP: How did it go when you did your next, and so far last, booth for the Armory Art Fair 2004?

KS: We tried again from scratch. The basic form was taken, in some respects, from the first booth but it changed. The poles were made out of plastic, very thin PVC, almost like tent poles. And again there was a desk that provided the support for the overall structure, which resembled a series of webs. The tent poles came out from the desk and seating element and arched over them, fanning into the shape of an igloo. There were two of these overlapping igloo forms, which served as hanging devices for the art. So there were just these really thin plastic poles crisscrossing and that created a kind of armature. It was wonderful because there was no separation between the inside and the outside: it was sculptural, it was architectural, it was incredibly useful, and it was functional. And you hung paintings on the outside of this apparatus, on the inside as well, and when you walked by or around it, you could see all aspects of a particular work. We hung things on the actual booth walls, and on the device. The desk was wedged in the corner, there were two seating elements, there were some different layers of shelving, and then the poles were all inserted; everything was of one form.

VA: With the first one we described where the desk was in the middle, one thing that bothered us—I mean 'us' the studio—and Kenny too is that we seem to have made a kind of corridor: A corridor for art. A corridor takes you in a specific direction, it's too closed. So here when we started, we still thought a desk was important, but we started in a corner. And that had a lot to do with what Kenny was saying about having different sized booths for different shows and maybe having something that could be adaptable. So we tried to make this system that could vary in size; it's not as adaptable as we would like but I think it does work.

CB: It makes you the center even though you're sitting in the corner because of this radiation….

KS: Yes, you were sort of hidden but you could see everything and feel everything. Though I was tucked away in the corner, it was great because it caught people's eye. But in the previous version there was an entrance and the veil of fabric, which created more of a separation than I was happy with and more than I think generally happens in the work of the studio. It is hard enough to get people's attention, but being only a little three-foot corridor, it gave people an easy way to just dismiss you (and they did). In the second version, when you looked you saw through, there was total transparency. Such intelligibility can either draw you in or you just keep moving along, but at least there was no mystery, you didn't really have to make a concerted effort to find out what was happening, if anything!

And in 2004 we were asked by Art Basel Miami to come up with a totally new concept together, which was to create some kind of a tunnel that would utilize a space that had never been used before to exhibit art. We thought maybe we would use the previous form from the Armory, but reconstitute it again and work on it more to make it fit into the unique space offered until it morphed into something totally unique. For this last incarnation of our booth projects the result was the most complex form to date, a series of three interlocking igloo shapes in a novel configuration with a totally new desk, shelves and seating structure. The only problem was that Vito envisioned the final element of the structure fanning out in such a manner as to block nearly 85% of the passageway from one side of the fair to the other. Word quickly spread among the dealers during installation that I was doing something to intentionally disrupt the functioning of the event, while in reality I was on the phone to Vito pleading with the studio to open the aperture more so as not to disrupt ingress or egress. That self-sabotaging I am not. However, the following year I was informed that I would not be invited back for 2005 and that Acconci's design was not what Basel Miami envisioned it would be prior to its implementation. Oh the joys of the art world.

LP: But you like to disturb the viewer and create things one doesn't expect.

VA: That's a kind of by-product. I do not wish to disturb the viewer. Our aim is to give people the chance to find something. In plazas, for example, there are benches to sit on, but some people choose to sit on the steps: that's a kind of rebellion. The bench tells me to sit down, but I'm going to sit somewhere else. I guess I would love to instill that spirit in the viewer, the impetus to find something instead of being confined to an assumed way of doing something.

What I liked about the booth for Art Basel Miami 2004 was its indeterminacy. It only grounded itself by having weights at the end of the fiber glass rods. If you wanted to extend it, you just removed the weights. The strange by-product of all those fairs was that you were always the center, the starting point. I wonder whether, in the back of our minds, we were saying that all this depends on the gallery dealer anyway. It has nothing to do with art; it has to do with the gallery dealer meeting the client.

LP: Were clients even able to see any pictures?

KS: In the three art fair booths that we did together, Vito always freaked out every time I went outside of his design to hang something on the walls beyond.

VA: That's because we thought it implied a failure on our part. We should have provided something that gave you all the opportunities you needed to hang pictures.

KS: Well, that's just the nature of this architecture being organic and fluid, which moves and creates a space within another space; there are all these other places and relationships and there are ways to approach it. In the past, I wouldn't have thought to hang a painting beyond this kind of structure within a structure. But then you see it and it seems so natural and it works.

VA: We created this structure with fiberglass, but Kenny wanted the white walls so badly, he would reach in between the fiberglass and put his pictures on the white wall. Almost behind the cage, but at least he had the white wall!

KS: We created a way to hang more art; we created a unique way to present two-dimensional works rather than simply mounting them on a generic white wall. We turned looking at a painting into a three-dimensional experience, where you could walk around a flat artwork like a sculpture. For me the gallery is an ongoing experiment; it's all work in progress, addressing how art is experienced, how the architecture dedicated to showcasing art is a mutable, non-fixed enterprise rather than how it has been shoved down our throats for in excess of 50 years.

KS: I also think there is a level of self-negation. What I find very interesting is that when you had the opening of your retrospective in July [to October, 2004] at the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Nantes and you were giving a talk, one of the first things you said was: I hate museums. At the same time you are sitting in a museum with a nice museum show. I think that Vito's work was a kind of anti-materialism in art; what you were doing in the seventies was this kind of anti-art.

VA: I don't know, did any of us think of it as anti-art? I'm not sure. Because in some ways it could only exist because of art. I was doing things supposedly taken from everyday life. People may burn the hair off their chest, they may tear out their hair. If you did that in a normal situation, you'd be put in some kind of mental hospital, but if you do it in an art gallery, they write an article about it.

KS: What I was getting at more precisely was the issue of conflict and the act of negating. I think your work grew to be a kind of institutional critique because of the stature of your career. As it progressed over the years you were welcomed into all these museums and universities, which would ordinarily be the greatest thing in the careers (even lives) of aspiring artists. And somehow you found that it was a dead end and evidence of a certain failure because your audience is so limited when you're preaching to the committed. So you had to reach beyond that, and architecture is a means of transcending that universe and speaking to a wider, general-interest audience. And when you posit that rather provocative statement "I hate museums," it's disingenuous to the extent that you made the trip and put together the show. I can relate to such incongruities, too—hating galleries so much and here I am opening my second one!

VA: I was giving a talk at a museum, with a little introduction and had to explain that I am an unlikely person to have a museum show because people of my generation resisted museums. We hated museums: the world was out there and the museum was here, with walls, which made a lot of us think: is art so fragile that it needs all that protection? The thing is, it does.

KS: As for hating galleries, I straddle the fence between the academic worlds, I write, I do some art, and I do eclectic projects. But commercially, I support what I do by selling art. It is this kind of conflicted state where 'I hate galleries' (but run them) that has really inspired and spurred me in my collaboration with Acconci Studio. Considering that you hate this system of disseminating art by putting it into the commercial pipeline—taking that as a jump-off point, how do you get involved in something that you need to do for economic necessity? If you have to do something that you loathe, how do you do it in a way that you can live with?

LP: What do you think about Duchamp's ideas about museums, was that influential on your thinking?

VA: It was tremendously influential. I think a lot of my stuff wouldn't exist without Duchamp: using the space in the museum as my mailbox. If Duchamp hadn't imported outside stuff into a museum, I don't suppose I would ever have thought in those terms. But Duchamp was a little too much of a dandy for me. He was too much above it all, full of judgment and irony. I was never a fan of irony; it's too clean. I've always preferred the messier, Marx Brothers' brand of slapstick humor.

KS: In a group show at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), you changed your address to MoMA and had all of your mail delivered there; thus you had to visit the museum in order to fetch your mail, and you turned your ordinary post and parcels into cherished works of art guarded by the museum staff. You might say that's a cross between clean readymade irony and messy slapstick humor.

VA: But obviously influences come from a number of places at the same time.

CB: Did architectural elements crop up for the first time in Instant House?

VA: Not really, there were installations starting in 73/74, but they were more like furniture elements. In the mid-seventies Sonnabend Gallery showed a piece called Where are we now (Who are we anyway?). The main room of the gallery was blocked off and the outside of the room painted black, so it became a kind of black object inside the overall room. A long table—a plank with stools on either side —was propped up on the window sill of the gallery and then went out the window. So inside the gallery it was a table and outside, a diving board. In a way, pieces like that were the beginning of two things: of a place where people could be (there were stools for people to sit down on) and of sound. A hanging speaker addressed people potentially sitting at the table. There is the steady sound of a clock ticking, a voice comes in "Now that we are all here together and what do you think Bob?" and "Now that we have gone as far as we can go, what do you think Barbara?" So I was trying to treat the gallery as if it was a town square, as if it was a plaza, as if it was a community meeting place. And I think in the back of my mind I started wondering if I was kidding myself. Here I am, doing these pieces in a gallery or museum, trying to pretend the gallery or museum is a plaza, a public space. It is never going to be a public space. If I really want a public space I better find a way to get there. It took me a long time, but I think it was a very important development.

KS: it reminds me of, say, Rikrit Tiravanija, who is quite an interesting artist. He did things like giving away food in a gallery (and still does) trying to propagate a social sculpture in the process, but I found it a little disingenuous. The only people that came in were people trying to get a free lunch, like underpaid critics who would go in 25 times to get spring rolls, it's comical. How can that kind of rhetoric be associated with social discourse when you're in a place with five critics, four graduate students and an art collector?

VA: I think we're confronted with an inherent contradiction. My work was part of that contradiction as much as his and that of many other people. It just can't be done. A public space needs to be a public space. If you're pretending it's one, it becomes a model of a public space where everybody is acting.

KS: When did you first go out into a square or plaza?

VA: Bad Dream Housewas probably one of the first in 1984, but it wasn't put in the most public space in the world because it was a college campus. At the same time I did a piece in a parking lot in San Francisco called House of Cars, but again it was under the auspices of an institution, a kind of alternative gallery. It did at least use a public space, people could pass through so it wasn't exclusively for an art audience. Those were probably the first timid attempts to bring stuff into a public space.

CB: Is there music?

VA: There probably should be, but there is none.

KS: There was in the bras, when you did the giant bras.

VA: Yes, there were speakers you could plug in… I guess every time I thought something was clear, it didn't mean it was clear to everybody else. Because whenever people were shown a bra they asked, "What music should we play?" And I said, "No no, it is supposed to be a speaker, like you play any music you want."

KS: Was it meant as an architectural form though?

VA: It was supposed to be furniture. It acts as light, it acts as a seat, and it acts as a body. They are all connected to the wall in some way, so I wanted the bra to have a wall, just like the body would have a wall: it's like the attack of a 50ft. woman, probably every male's fear. What I thought was wrong with pieces like Bad DreamHouseor House of Carswas that they're public, anybody can use them, like a public playground. Something is called House of Carsbut you can't really live there, there is no bathroom, no kitchen, so 'house' was a lie. If I called it a 'playground of cars', then I wouldn't be lying because you could use it to play.

KS: But people certainly did use House of Cars.

VA: Yes, they find some way to go to the bathroom, I didn't find one, they find some way to cook food. And I thought, I am cheating, I am not taking this seriously enough. Not that everything has to be a house, there are public spaces you go through and you just visit, but it kind of bothered me that I arrogantly called something House of Carsand Bad Dream Housewhen I was pretending.

LP: Is that why you started "Acconci Studio" in 1988, the name of which even indicates collective authorship?

VA: Yes. Now, we want to change the name of the studio again. And not just change the name; we want to change the whole structure. We want it to be a partnership of four people. The three people I work closest with. And two of them have been there for a long time, like 7 or 8 years. I think that there is something wrong; it's horrible that it's always me no matter how much I emphasize the studio.

KS: That has something to do with the cult of personality and branding.

VA: When I say Acconci Studio, people always say VA. There might be an article about us in the fall New York Timesmen's fashion. When the photographer came, we talked him into taking a photo of the whole studio but instead they're only using a photo of me and not of the whole studio. In 1988, I kind of assumed that my name was too much of a known quantity, that I couldn't get rid of it. But I wish I had given it a different name so that it would have been a new entity. I shouldn't think it's too late. The studio has to be a partnership, it can't just be one person. We tried to put names together. And I even made an appointment with an accountant to see how this would change the whole structure?

LP: What names have you thought of?

VA: I don't know if it would be a combination of names, first names or last names, or some other name, like Asymptote, Plasma or any number; this is the time of architecture group names.

KS: What do you think about the role that ego has played in the past? How did you relate to the studio in the beginning, did you always want to subordinate your name?

VA: I think I founded the studio because I wanted to do something I didn't know how to do alone. I probably assumed that I would work with people and that their ideas might weave into mine. Maybe when I started I did think that my ideas were more important, but I think that's changed totally. Even now though, would I totally accept as a studio project something that I didn't have anything to do with, and just other people in the studio had something to do with? I don't know. Probably not, but I have the feeling I should.

LP: But what's the difference between being an artist and being an architect?

KS: In New York, they have this law that when you build a new building you give one percent of the budget to art, and Vito said I don't want one percent, he was more interested in the other 99%. And there is another thing we have in common: the art world is all about restrictions, who is welcomed to the table and who is not and everybody is pigeon-holed. Vito was interested in bigger audiences. He was preaching to the committed when they came to a gallery. Now the art world is bigger than it's ever been in history in spite of the art world mentality. I think that's what drove Vito out of the galleries: the small-mindedness of the people.

VA: I'd say the same thing in slightly different words. I want people to happen upon something, rather than to go to a place where something is presented to be looked at. I'm more interested in the casual passerby in the city, who stops at something, not because something is announced as art, but because it connects with that person's life. I always think that you learn things more not from something that you've been told to study, but from something that just happens when you're in the midst of studying something else. And for me there's another big difference between working as an artist and working as an architect: in architecture you create something that people will be doing something else in the middle of, but whatever you present as art is given some kind of focal point. Maybe this comes from the interest that I always had in music and sound. I'm more interested in providing a kind of ambience, inside of which you can do all kinds of other things.

LP: Could the ambience be perfume too, like "Rotterdam," created by Herzog & de Meuron?

VA: We've been thinking about perfume a lot. But we haven't done anything yet.

KS: I can only image what Eau de Vito would be like!

LP: And in terms of music, do you have anything specific in mind?

VA: I have always loved the music of the Doors, but when I love it, I love it for me then, in the past. I don't want a world of the Doors now.

KS: You want a world with no doors, which turned into an architecture with no doors, or walls for that matter...

I mean listening to music for the first time is for me like meeting someone that you never knew before. When you first buy music, or come across music, and you listen to it, it's almost uncomfortable. You have to make an effort to get your mind around this new sound and then decide whether or not you like it, and I guess once you are familiar with something you react on a subconscious level, and then it's completely changed…

VA: I think music is probably easier to connect with a particular time. So now you start to know what the 60s are. And in the mid 90s, when I first heard things like Tricky and Moby, I finally thought like, wow, now I can get the 90s.

KS: How do you get access to new music?

VA: It's hard for me. I go to a music store in New York, 4th Street where they have a lot of little blurbs and little texts written by people in the store. So you make guesses, you buy 40 things, maybe one thing is good. But I've come to the realization that my work is only worth something when it is connected with a particular music at the time.

KS: But how come the music is almost non-evident in your work, for something that is as influential as you stated in the past. I mean there are pieces, these learning pieces, when you sang songs, maybe it's in the intonation of your voice with your ranting and ravings. Perhaps the music is there but it's just a pared down notion of music, as your voice is the most distinct part of your persona, recognized the world over, and I suppose it is ultimately very melodious and tuneful in its own right.

VA: There is a videotape of 1973 called Theme Song, where I am playing things like the Doors, Van Morrison, Neil Young, and I am trying to start a relationship with the person looking at me on the monitor by means of these songs. So the Doors say "I can't see your face in my mind" and I say "of course I can see your face and I am going to start some kind of relationship with you." So I was trying to use the music as an anthem, as a theme song for a relationship that I was going to start with this unknown person. And then the relation has to end by the end of the tape. It has to be fast: we make a relationship, we live quickly, and we leave each other by the end of the tape.

But at the same time you're right, it seems like the more recent stuff, the wall should be filled with electronic music.

KS: In your architecture?

VA: Yes, because I think there is no secret about what kind of music I am listening to now: Plastic Man, Vladislav Delay, Aphex Twins, it's all kind of pop-electronic music. Why? Because you don't have to pay so much attention; it's like wallpaper, like a surrounding, an ambience. I think music and architecture are inherently connected. And architecture and sculpture probably have no connection whatsoever, simply because you cannot go inside sculptures, you're not supposed to go inside sculptures.

KS: You can go into some big, heroic, machismo Richard Serra sculpture where you are meant to be awed by the scale of the piece and the foreboding heft of the rusted metal.

CB: Or Niki de St. Phalle's Sculpture Hon. You could enter it and there was a milk bar inside.

VA: But I think when things like that happen, sculpture becomes architecture. I think Serra is right, that in order for a sculpture to be sculpture you can't have anything to do except look at it.

KS: And then you made that comment that you would have liked the work more if, after venturing into the center of the spiral, you had found a hot dog stand waiting there. I'm sure that comment would be much appreciated by the metal master himself!

VA: I love a lot of Serra's sculptures, I just wish that when I got inside, I didn't just have to see god, I wish I could eat something, I wish there was a restaurant there. I think there really is a difference, and I think that's the problem with art, there is no function.

LP: But Acconci Studio also sets up certain architectural rules of behavior.

VA: I wish we didn't. Ideally the kind of space we would like to do would be a space that has some kind of skin. When you want a seat, you would pull the skin out. And when you don't want it anymore, you push the skin back.

LP: Like in the Clothing shop United Bamboo in Tokyo, where you can fold out your own dressing room?

VA: We want architecture to be in the hands of people. I have this nagging doubt: Is architecture inherently a totalitarian space? When designing a space, are you necessarily designing people's behavior in that space? I want us to do the opposite. Why do we, me and 200 other architects in the world, all make places that evolve, twist, warp. We obviously want spaces that work as biology. We want a space to live, to live not as a monster that overtakes the person, but as something that reacts. Action is great, but transaction is better. Action is ultimately private; transaction lets other things in as well. We would love to make spaces that would actually react to people, as people react to those spaces. I don't know really how to do that yet.

Cristina Bechtler: There is a young architect in Paris, François Roche, who made this space in a swamp somewhere in Trinidad, where the mosquitoes would remain between two walls that are moving. I can't explain it, but the whole thing looks like an amoeba. It's twisted and the façade is constantly moving.

VA: That sounds very interesting.

KS: Like you were saying before, you were looking at all these twists and turns, but with all these twists you still end up with just another four walls.

VA: I think that what most of us want is twistability rather than twist. That it can twist further, that it doesn't stop at one twist but should go on twisting, should go on bulging. I don't think it's about the making of shapes—it's the making of a changing system.

LP: Like a living animal?

VA: On the one hand, it's a skin that lives on its own power, and on the other, it can be adjusted by the people using it. The fact that you can use it like clothes—architecture as clothing—is really important. Clothing has become more and more important to us. A lot of my writing makes comparisons to clothes. Clothing is the first architecture of the body. Probably architecture comes in steps; first there is the body, then the body covered by clothing, then the body with clothing covered by an armchair, then the body covered by clothing covered by an armchair covered by the walls of a room. We haven't gone far enough yet; Serena [Serena Basta, Assistant of VA] has worked on this mostly. She was probably more interested in it than I was in the beginning. She wanted to start with something very cheap, very readily available. She started with t-shirts, a T-shirt that you could buy for a dollar. We've been knotting T-shirts together, twisting T-shirts, using t-shirts as the most commonplace material. I don't think I would have come up with that myself, and I'm glad she has. I've always liked the idea of clothing as something to ...

KS:… to express yourself?

VA:… more to protect yourself. And she's brought in more expression. Some of the things made out of such cheap materials almost end up having a kind of glamour. All that knotting makes it a kind of chaos, things that come from the shoulder move down to the floor. And things that I never would have thought I was interested in have started to interest me a lot. Especially in combination with what we're doing now—the notion of styling, like the styling of a car, which never interested me before.

KS: But the worst kind of scenario is when styling evolves towards some kind of formulaic brand-like architecture. I went to see one Daniel Liebeskind building, and then saw another he had just done in London, where he uses this kind of personal vernacular language. And the departure from one building to the next was just a Liebeskind building. Fashion and style can be tricky.

VA: But, as an example, you're using an architect who wants to think about architecture as a kind of religion. And I don't believe.

KS: With the fashion-thing the downside is that, once you come up with these great torn, faded, twisted t-shirts, you've got to come up with something else. Obsolescence is built into it. But was it your idea to ultimately market this stuff?

VA: Yes. I think distribution is important. For Serena it was very important that we sell these for 5 dollars, but people we have talked to said you can sell this for 350 dollars. If you sell it for 5 dollars, someone is going to make another version of it and sell it for 700.

KS: But if you sell it for 750, someone will knock it off and sell it for a fraction of that. Maybe the high price market is better. It's like with art. It's harder to sell a masterpiece for 5,000 dollars than it is to sell a known artwork for 500,000 dollars. If you are selling shirts for 5 dollars, you have to sell a hell of a lot to pay rent for the month. It's a tricky thing, the dynamics of the marketplace. But you could do different versions, like a 5-dollar version and a more exclusive version.

LP: Are you involved in fashion too?

KS: I had a legal education; then after law school, I went into the fashion business. I went to museums, but I was so sheltered where I was brought up. My family had no connection to art whatsoever. I thought that art went from the studio into a museum. I was unaware of any commercial enterprise built around art. I wanted to do something creative so I thought about becoming a fashion designer. I actually started working for this Italian designer of men's neckwear, like Willy Loman [in Death of a Salesman], carrying these huge suitcases all over the east coast of America, trying to sell these things. I thought I would teach myself the business from the bottom up—a very hapless, unsatisfying experience.

CB: To my mind, some of your projects, like Flying Floors, refer to deconstructivism. Are you aiming at a form of destabilization? Or is it more a question of enhancing awareness of space or the conditions of existence?

VA: I think there is an urge to destabilize or to unstabilize. Architecture is a kind of de-architecture at the same time. I think our hope is that when people use our stuff, they become liberated. I don't know if they can be. But I don't think we would want to do something if we didn't think we can now free people. If you make a space that is turned inside out or that is turned upside down or turned on its side, maybe a person will start to think that the world isn't as fixed as all that. Maybe that doesn't mean a destruction of use but rather a use that we wouldn't have thought about before. What happens if I turn this upside down? Water would fall. And maybe that means that I can now wash my face, and I couldn't wash my face before. Other things can happen: you might lose certain things, but you also gain things that you didn't know were there. So if you turn something upside down, if you turn something inside out, if you stretch something, if you cut something, maybe if you perform, something new happens. That's why, to me, the notion of architecture is always a notion of some kind of action, some kind of performance.

LP: This also has a direct impact on the people moving in the architecture and, in turn, reacting to it.

VA: When you think of spaces for people, you think of how people are going to be there. It is about ways to live. Of course, most of the time we aren't doing a house, we are doing a public space. So we ask ourselves what if a large group of people wants to gather? And if you're doing a democratic space, you have to think, what, if in the middle of that large group of people, there are two or three people who want to be alone? So you're going to need spaces where people can move away from the public eye. But then what about the single person who might be thinking about suicide or might be thinking of serial murder? Maybe that person has to have a place too. So you think about different spaces for different kinds of activity, but so far the only way I've figured out how to do architecture is that things in the world exist. Land exists, buildings exist, and since they exist, you want to perform operations on them: you can renovate something or you can add something. Renovating doesn't necessarily mean to tear down the old but you can surround it with the new, you can take away from the new, you can insert the new. Rome has done that automatically. And that, to me, can only make things better because you never know what is going to come later. But when something does come later, why not add it to the past, you can reconsider. You can never recreate old times, so why try. The materials are different and the technology is different.

KS: In England they are dictatorial about replicating aspects of Victorian or Edwardian architecture. It is unbelievable how tight the controls and protections are in order to preserve and effectuate certain historical styles of architecture in certain neighborhoods at the expense of the new and contemporary. You can't even change the look of a windowpane or dormer.

VA: It is not that I want to get rid of the old, but I think the best way to deal with it is to revise it. We see the old with the eyes and minds of now. So we have a kind of advantage. The most horrible thing about architecture, though, is that it is inevitably outdated once it is built.

KS: But anything that has certain characteristics of quality—whatever that may be--will last somehow. You can look at certain buildings a hundred years later and they still seem fresh.

VA: But in order to do that you almost have to isolate them from the rest of the city. And architecture is in the middle of the city. The city changes, but your design doesn't.

KS: That reminds me of Marcel Duchamp who said that art should have a shelf life, which is quite a beautiful theory. There is no reason for art to be a canon carved in stone.

VA: But the great thing about architecture as opposed to art is that everybody knows it's going to be renovated, probably starting five minutes after it's been built. People think of uses they didn't think of before, they need more space, need different kinds of spaces. So architecture is always a kind of kernel that is going to have something added. That's something like shelf life.

LP: Most your projects are, in fact, renovations or expansions of existing buildings.

VA: Nobody has asked us to do a real building!

KS: But you did a private home in Greece.

VA: It was going to be a kind of weekend house in Calamata. We made one initial conceptual proposal, which was kind of strange actually. They had given us a really flat site and to counteract that and because there were two brothers, we made a house with two intersecting spirals. Strangely, I had never been to Greece before I went to this site. What struck me, being there for the first time, was this kind of extensive balcony life. So we tried to make a house where the roof of one brother's house acted as the balcony for the other brother's house. When they saw it they claimed that they really liked it, but, because it was spiraling up, they thought we should do it on a sloping site that would go down to a river. Then he said he would get this other site, but he never called us again.

KS: But I asked you to do a theoretical house for me.

VA: That's true. You asked us to do so many things. We started to think about this theoretical house and then there's an email from you saying, do a car.

KS: I'm interested in design, industrial design, I'm now working on a publication that deals with art, architecture, and car design. This is something that isn't looked at closely. Typically, when you want to look at cars and read about them, you have these magazines for piston heads, car fanatics. We spend so much of our time in cars, experience so much through them; why not make a closer analysis as to how they are made and what the design is. I would like to do a garbage can, a car and few things in between.

VA: This is good, except that we can't keep up with you: do a garbage can, do a bathroom.

LP: Now you're working on the new project with Zaha Hadid in London.

KS: My present temporary exhibition space at 33-34 Hoxton Square in London's East End will be demolished in 2005 and a mixed-use commercial and residential building designed by Hadid will take its place. The façade will be glazed, the lines demure and the roof a curved, heaving and falling masterstroke. Some of the self-assured outlines and ripples of Hadid's upcoming project are reminiscent of the shifting walls and furniture in the former Acconci interior.

LP: Why didn't you contact Acconci Studio for this project?

KS: To be honest, I'm in London, so I hired Zaha Hadid to do a building there. This is less of an exercise. In the end, I might not use the building at all. I'm looking for economic models that would enable me to leave my active day-to-day participation in the art world. It is like when Vito moved away from art and was kind of reticent. The art world has changed so radically in the last 5 to 10 years; it's become a different animal. I just don't really have the same kind of passion to hit the trenches, ferret out artists, and do the kinds of things I did in the past when it was more exciting to me. I'm interested in trying to do other things. The first thing I did when I moved to London was to plan to build a building, and the building will contain flats and commercial space. It's not that I don't have faith and trust in the studio—quite the opposite of that. It's just more pragmatic for something on the scale of a complete new build where day-to-day decisions on site will be necessitated. Nevertheless, during construction of the Hadid building on Hoxton, we will open yet another Acconci designed space at 17 Britannia Street W1 in Kings Cross.

LP: Just what are you planning to do?

KS: The first idea that Vito came up with was a series of tracks suspended on the horizontal beams in the space, like passageways along which people would walk through. It would be on tracks, with elements that would come down, like the ones at the Art Fair booth for the Armory Show 2004. It was an idea that incorporated a lot of those elements but there was more fluidity to it.

VA: Yes, that was another example where we tried to have a painting with no walls behind it, where the painting would be suspended in the space; walkways would take you to and away from paintings. There were horizontal beams cutting the space in half. So we thought, let's use these horizontal beams for a walkway system.

LP: Is this a new gallery space?

KS: No. I've never been interested in an art gallery. A big part of the reason I ever opened a gallery was the opportunity to work with Vito. And to try to do something very different from the way galleries are today. And having worked on this one building with Zaha, I'm negotiating for another building. In the meantime I have rented another space for 3 years. I'm in the midst of working to present a situation that will provide a reasonable building context for the studio.

VA: Kenny is taking so seriously what I've said about architecture being outdated that he gives us spaces that only last three years! They don't have time to grow old.

KS: The beautiful nature of Vito's architecture is that it is often not a fixed thing; it's not just a wall dictating the border of a space or a door dictating where you come in and exit. The space we did together looked like an orchestra of architecture, the walls moved, they mutated into something else. So it is not so much a subjective contemplative thing, and it isn't this finite, fixed typical thing that you would associate with architecture: a building with the doors here and the windows there. Instead it's participatory, it's not fixed.

VA: Obviously we are not alone in this respect. There are a lot of architects now that we are interested in: Foreign Office Architects, MVRDV or Asymptote. People are very much thinking in terms of 'can you have a space that shifts?' It's a topological world, a computer world. People think more in terms of shifting boundaries, probably because so many political systems in the world are at their most conservative now, it's probably the last gasp of nationalism. We're heading for a world of nomads where countries don't exist anymore, so we desperately want to maintain boundaries, we desperately want to keep immigrants out. The more 'home' becomes a fluid, vanishing concept, the more we cling to it.

LP: How do you distinguish Acconci Studio's from those of other architects?

VA: Sometimes I think that so many people's work looks so much the same. And why is that? Is it for the horrible reason that we're all using the same computer programs? Or is there something in the air? Something in the air about this twisting, warping? Just like in the Renaissance when perspective was invented; everybody's drawings probably looked the same for a while because nobody knew how to use the new tool yet. Then eventually you find out what kind of new thinking is made possible by the new tool.

KS: The same thing applies to art. We're communally exposed to the same media, the same internet, books, magazines, and music, etc. Art reflects the times. So when you visit artists the world over, they could conceivably all make the same piece. And many times I have come across artists whether in different countries or different neighborhoods making the same exact art as someone else.

VA: I was very conscious of that at the end of the 60s, the beginning of the 70s. Along with a number of people I knew in New York, I was doing stuff with my own body. The most important distribution engine was a number of little magazines that started at the same time, like Avalanchein New York. The best part of it was that you began to realize that you are possibly not crazy. Maybe it was the zeitgeist, something that came from demonstrations against the Vietnam War, and LSD might have been the agent, but I was never really attracted to that.

KS: Some of my friends did it.

VA: The computer somehow seems analogous to LSD because it makes the same kind of movements. And you get more possible information than you ever could have had. You can use a computer program and you can have a line and suddenly this line starts to connect itself. This should actually be the most exciting time that ever existed. This should be a time that makes George Bush impossible.

CB: Well, doesn't the computer also erode hierarchy?

VA: For me that would be a goal, but maybe not for everybody. The studio wants to eradicate hierarchy because I think it gives people more choices. Architecturally speaking, that means that if you have a wall that is not necessarily a wall, it no longer separates inside and outside. You still might want to separate them, but you have a choice, it is not predetermined. If our architecture has a goal, it is about mixing, being simultaneously private and public, here and there. I am here and I can point, and as soon as I can point, I am here and there at the same time. It would be great if architecture could do that, if it could be here and possibly fly at the same time.

KS: Do you spend a lot of time on the computer yourself?

VA: Besides using it as a word processor? Yes, I google a lot to get information, but I don't use architectural programs. I'm there when people in the studio do things. I do things that people using computers hate, I touch the screen a lot, saying let's move it here, let's twist it here. I insert the unnecessary body into the computer world.

LP: Before the computer, was your instrument more language or drawing?

VA: Both, language and drawing. But the kind of drawing that nobody could possibly understand except me. Although, when people had worked for the studio for 3, 4, or 5 years, they totally understood what nobody else could understand. Even hand movements. I started to realize that am I embedded in the notion that the only way to think is through language. Then I noticed that I used my hands a lot. I was going from verbal thinking to spatial thinking.

LP: Can the architectural projects exist without the texts?

KS: He wanted to put all those descriptions to use, all those great descriptions he has written for just about everything that has emanated out of the studio. Sometimes I think that all the actual art, the photo/text pieces, the performances, the sculptures, and installations were all just excuses to write about the art. The works are merely illustrations for the text!

VA: I'm not sure. Yeah, they might be. But they are fiction, I think. Recently we made a few, when we applied for some open architectural competitions and where you are not supposed to send a proposal first. Then I do a text that comes before we have tried to draw anything. I think those are some of the best texts I have written.

LP: Can you give us a concrete example?

VA: It's a kind of brief fiction about: what if such and such would happen. We applied for a competition about building a research station in Antarctica—we weren't even chosen to make a proposal—but it started with me trying to get a notion of what this project could be. It started with language saying: come into the dark. It's mostly dark there. This is a place where you have very, very little light, so when there is light, it's sort of all white, because it's all ice. So we have darkness and ice. What do you do? You can't really build there, because of the snow; there are no foundations. So you have a building that would try to surf the ice, the way you would surf water. And it's all black and white. I might not work it out as extensively as that but it probably would start with a very, very short story.

Another example is related to the clothing stuff and some kind of utopia. Serena wrote a little, kind of theoretical text about a place called No-Men-Landand she thought that it was connected to the clothing and she wanted me to write a more story-like text. What came out was a fiction about a place that could either be called No-Men-Land or Noland.There were certain problems, the women could leave No-Men-Land/Nolandfor a while and could go to this other land to get pregnant. So they developed a system, a kind of code consisting of all sorts of different flowers, so if you wanted to get pregnant you got one of these flowers and you would insert the flower. A rather long story that doesn't seem totally or at all connected to the clothing we've done so far. But it will probably lead to something. It's a good basis.

LP: Writing is important to you too, Kenny.

KS: I write about very different things, never in the sense of a critic, just the sociological things that happen now in the art world or the economics of it—just the way things function. And then more personal things, it just covers the gambit. But your texts, your voice is much more important. It was an indispensable part of all your early works and it also figures audibly in the retrospective in Nantes.

VA: It is all over the place, even narrating the architecture films, you hear it from monitors and from speakers. Corinne Diserens is right, the basis of my work is language, and maybe voice even more so. Because there is a real difference between spoken language and written language. Written language you look at, spoken language is the beginning of architecture….

CB: When does the spoken language begin to become architecture?

VA: Obviously spoken language came before written language. But written language is almost the equivalent of art, it is in front of you. Maybe I can get at this in a roundabout way because it also has to do with what my resistance to art was from the beginning. In art, in spite of different attempts to nudge tradition, the standard of art, the convention of art is that the viewer is here and the art is there. So the viewer is always in a position of desire, you look at what you don't have; you don't have it in your hands. Because you don't have it in your hands, that position of desire is a position of frustration. I think a long time ago I began to do art because of resentment to do-not-touch signs in a museum. There is a reason for do-not-touch signs, but still, they imply that art is more expensive than people. Just as when we do architecture: we think of architecture as an occasion for people, yes, it is made out of forms, it is made out of shapes, but they are secondary, they only give people a place to do actions, do events.

CB: Did you ever publish your poetry?

VA: Yes. In some little magazines. MIT is putting out a book on the poetry now.

CB: Do you still write?

VA: I always write. I always assumed that when you do a piece, you do a description of the piece. Obviously other people don't do that. Sometimes I wonder, do I go through all this effort just for a half-page description. The problem is writing is still the most important thing to me. I don't think anything is done until it's written, until it's in words.

CB: But writing is kind of immaterial, language is more virtual than anything else…

VA: Yes, but when I was writing poetry, I was trying desperately to make words be matter, to make words be material. That came not from other writing, but from Jean-Luc Goddard movies. There would always be a statement and then all of a sudden the camera would zoom in to the middle, so in the middle of the word you get another word. In that middle of the word, one word would break up another word. What interested me in language was the amazing indefiniteness of it, because in almost every world you can find a little world that probably contradicts the big world. [world or word?]

KS: If you consider your architecture as falling somehow within your oeuvre, it is a continuum from your early work to what you are doing now. And I think it's amazing how you are always pushing yourself into uncomfortable, unsafe choices…

VA: I didn't grow up thinking I was an artist, I grew up thinking I was a writer. There is a very different notion with writing. You don't think of t h i n g s, you don't think of a book as a thing. Ok, maybe the first edition of a book has some kind of value, but that's a marketplace value. I think with writing you just think something is going to be distributed to readers. So the notion of a thing that exists probably doesn't exist in the mind of a writer. I don't think I have ever thought in those terms.

KS: What did your Dad do?